A recent article in the New York Times asks whether “North Carolina is the future of U.S. politics.” The article describes the state’s contentious political battles – most notably on House Bill 2, otherwise known as the ‘bathroom bill.’

One explanation given for the state’s political divide is a topic we’ve recently covered here at Urban2Point0: the concept of ‘two North Carolinas’ (we’ve called it ‘a Tale of Two States’). The author argues that:

The State’s metropolitan areas continue to prosper, with an influx of white-collar workers drawn to their thriving finance and technology sectors. But in North Carolina’s rural communities, the tobacco, textile, and manufacturing industries have collapsed, with little taking their place.

These economic disparities – and their relationship with areas either economically growing (where residents are more liberal) or shrinking (conservative) – exacerbate North Carolina’s partisan divides. The article quotes a state senator from rural North Carolina as upset about announcements of firms moving to Raleigh or Charlotte, arguing that “it’s like fish in a barrel.” He worries that efforts to attract firms and residents to cities will result in North Carolina losing what he feels are its traditional roots.

In this post, we’ll provide additional context to the New York Times story using data from the A Tale of Two States series. As in our previous posts, we’ll examine changes in private-sector employment between 1990 and 2015. (If you’re interested in probing these issues deeper, we recommend reading our previous posts on the subject.)

The growing service sector economy

The U.S. has seen its economy shift from manufacturing to the service sector since the 1970s. North Carolina is no exception to this trend. Between 1990 and 2015, the state’s fastest-growing industries were professional services, education and health care, and hospitality. In fact, the service sector comprises the top six fastest-growing industries in the state, and seven of the top eight.

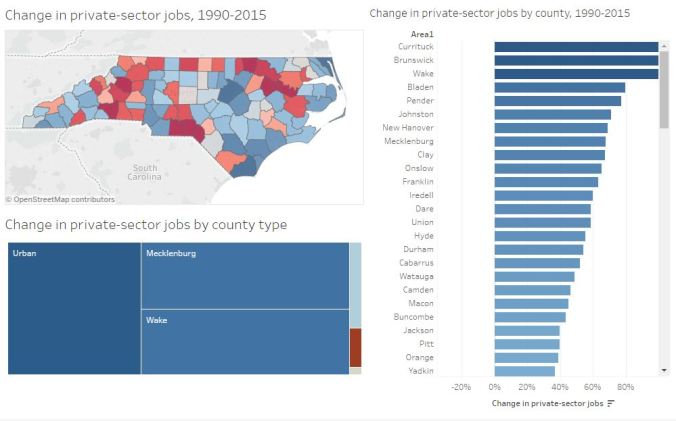

One finding from A Tale of Two States is that growth of service-sector jobs across North Carolina has been strikingly uneven. Urban counties have gained hundreds of thousands of jobs while non-metro counties – including small towns and rural areas – have only gained a small number or even lost jobs. Between 1990 and 2015, metro counties added nearly 739,000 jobs, while rural and small town counties lost over 6,000 jobs.

click above image to interact

Concentrating growth in urban areas

This disparity between metro and non-metro counties is evident when we examine job growth in the service sector, which has accounted for nearly all of the state’s new jobs. Counties in metro areas are classified as either urban or suburban and are in shades of blue in the figure below. Non-metro counties are either classified as rural or small towns and are in shades of orange. We’ve separated Mecklenburg and Wake Counties because they account for so much job growth.

click above image to interact

For nearly all service industries, metro counties have accounted for at least 90% of private-sector job growth. In fact, for each industry, at least half of all job growth has occurred in just two counties: Mecklenburg (Charlotte) and Wake (Raleigh). Given that these two counties only account for 10% of the North Carolina’s population, one can see how service jobs have disproportionately clustered in these areas.

click above image to interact

Even more worrisome for non-metro counties: for the highest-paying industries in the service sector, job growth is even more concentrated in metro areas. For example:

- Information: 100% of all job growth in metro areas (Mecklenburg and Wake Counties to be exact); average annual pay for these positions in North Carolina is $76,624.

- Finance: 92% of all job growth in metro areas; average annual pay is $78,029 statewide.

- Professional services: 91% of all job growth in metro areas; average annual pay is $58,748 statewide.

In comparison, the two service-sector industries where non-metro counties have done slightly better – education and health care in addition to hospitality – have annual average salaries of $44,753 and $18,236, respectively.

Are there policy responses?

North Carolina’s experience of urban growth and rural decline is not unique: across the U.S. and industrialized world, service-sector jobs are concentrating in cities and metro areas.* Scholars have proposed several reasons for why this is occurring. These include:

- College graduates generally prefer to live in cities, so locating jobs in urban areas makes it easier to attract employees.

- Service industries don’t occupy as much land as manufacturing, so firms are less sensitive to the price of land (which is much higher in cities than rural areas).

- Service industries – particularly finance and technology – benefit from being in proximity to one another, particularly from their employees interacting with those at other companies. This is easier in cities than in spread-out rural areas.

The New York Times article quotes State Senator Ralph Hise as arguing that “it’s really going to take workforce development and recruiting and economic incentives … to tag those industries that can come into this state and serve in one of the rural areas.” Some Southern states – notably South Carolina (Boeing and BMW) and Alabama (Airbus and Mercedes-Benz) have attracted manufacturing with incentives.

It takes substantial funds, though, to attract these factories, and competition among states is fierce. Further, new manufacturing facilities often piggyback off previous ones. North Carolina’s inability to attract manufacturing in the past may hinder its ability to attract factories now.

North Carolina may consider incentivizing other industries for non-metro counties. The state has already enjoyed some success attracting logistics firms, which can then help attract manufacturing and warehousing businesses. Any efforts to attract jobs to rural areas, however, shouldn’t be at the expense of efforts to attract service-sector industries to urban areas. Ultimately, an approach that leverages North Carolina’s strengths in finance and technology, and its emerging logistics sector, may be the best path for economic vitality in all parts of the state.

* A very quick calculation shows that approximately 93% of all private-sector job growth between 1990-2015 occurred in metro areas.